|

Why are some countries much poorer than others? Why does the gap between rich and poor countries remain wide over a long period of time, irrespective of e.g. technological advances and economies' openness? Various explanations are given in the literature, wherein some philosophers, economists and other scientists emphasize the role of Nature (i.e. physical and geographical environment), while others consider man-made factors shaping human incentives as more fundamental causes of countries' (under)development. Below the main explanations (or hypotheses) of comparative economic growth are discussed, particularly focusing on the role of institutions in the process of economic development. The ignorance hypothesis: Leaders of poor countries and their (economic) advisers do not really know how to make their countries rich. That is, it is believed that there exist a lot of market failures in poor countries, but policymakers and their advisers do not have a clue about how to fix these problems; on the other hand, rich countries have access to good policy advise and solve market failures successfully, encouraging economic growth. This story, however, is very naïve and lacks empirical support. The geography hypothesis: Differences in geography, climate and ecology explain cross-country or continent-wide differences in economic performance. It is often claimed, for example, that countries with temperate climates have a relative advantage over (semi)tropical areas. There are different variants of this hypothesis, which, among other interpretations, include the following explanations:

The culture hypothesis: (Under)Development is primarily caused by differences in cultures, religions, beliefs, values, practices, and ethics. Typical, but some very delicate and highly controversial, explanations include:

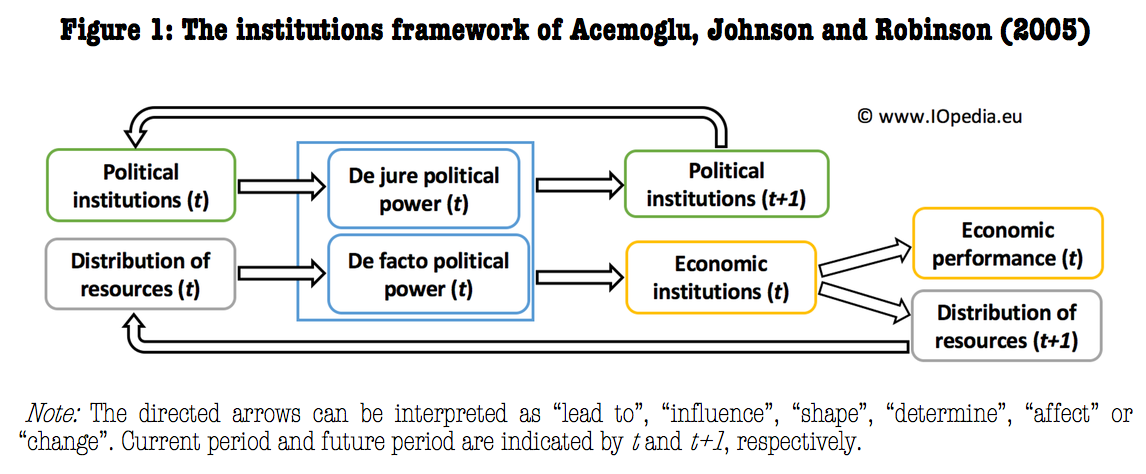

However, it has to be noted that neither religions, nor "national cultures" like Anglo-Saxon vs. Iberian heritage, or European vs. non-European cultures, nor any other sets of beliefs could fundamentally explain economic prosperity of nations. Beliefs themselves are shaped, modified and determined by institutions (to be discussed below) and the evolvement of institutions throughout the course of history. Similarly, the example of North and South Korea can serve as a strong contra-argument against the hypothesis that culture and geography are the fundamental causes of economic growth. These two countries were largely exactly identical both culturally, geographically and in many other important respects (such as ethics, language, history and other potential determinants of economic growth) before their separation at the end of World War II, but thereafter were organized in entirely different ways. Today we observe huge income disparity between the two countries. For curiosity, just Google "North and South Korea at night". The institutions hypothesis: Differences in economic institutions cause differences in economic performance, and generally institutions are the fundamental cause of income differences and long-run economic growth. To understand this explanation, one has to know what institutions exactly mean. Douglass C. North, a world-renown economic historian, in his 1993 Nobel Prize Lecture gives the following definition of institutions: Institutions are the humanly devised constraints that structure human interaction. They are made up of formal constraints (rules, laws, constitutions), informal constraints (norms of behavior, conventions, and self imposed codes of conduct), and their enforcement characteristics. Together they define the incentive structure of societies and specifically economies.” (emphasis added) Institutions should not be confused with organizations: the latter consist of individuals that act together for the purpose of achieving specific common objectives. As emphasized by North, If institutions are the rules of the game, organizations and their entrepreneurs are the players… Organizations include public bodies (political parties, the Senate, a city council, regulatory bodies), economic bodies (firms, trade unions, family farms, cooperatives), social bodies (churches, clubs, athletic associations), educational bodies (schools, universities, vocational training centers).” – Douglass North, 1993 Nobel Prize Lecture A simple, yet quite useful, framework for understanding the role of institutions is proposed by Acemoglu, Johnson and Robinson (2005, henceforth AJR). The AJR framework is visualized in Figure 1. In this framework, political institutions and distribution of resources (e.g. the distribution of wealth, of physical capital stock, of human capital) are the so-called state variables since the two: (a) typically change relatively slowly over time, and (b) are believed to be the ultimate determinants of economic institutions and economic performance. The framework emphases the concept of hierarchy of institutions, wherein political institutions determine economic institutions, which in turn lead to a particular economic outcome. There are two sources of persistence in the AJR framework: (1) political institutions evolve slowly and often a large change in the distribution of political power between its two sources (de jure and de facto political power) is necessary to change political institutions (e.g. transition from autocratic regime to democracy), and (2) a richer group, relative to other groups, will have more de facto political power, enabling it to shape the economic and political institutions in its favor. These two sources of persistence are illustrated by reversed arrows in Figure 1, creating circles. Depending on whether a country in question possesses inclusive institutions or extractive institutions, the system generates a dynamic process of either positive or negative feedbacks, which in turn further and gradually increase, respectively, institutions’ inclusiveness (pluralism) or exclusiveness (absolutism). Thus, such dynamics result in either virtuous circles or vicious circles. In order to encourage all individuals to take part in economic activity, to take risks and invest, to innovate, to educate themselves, to learn (e.g. new technologies) and then give the fruits of their education and expertise back to society, there must be:

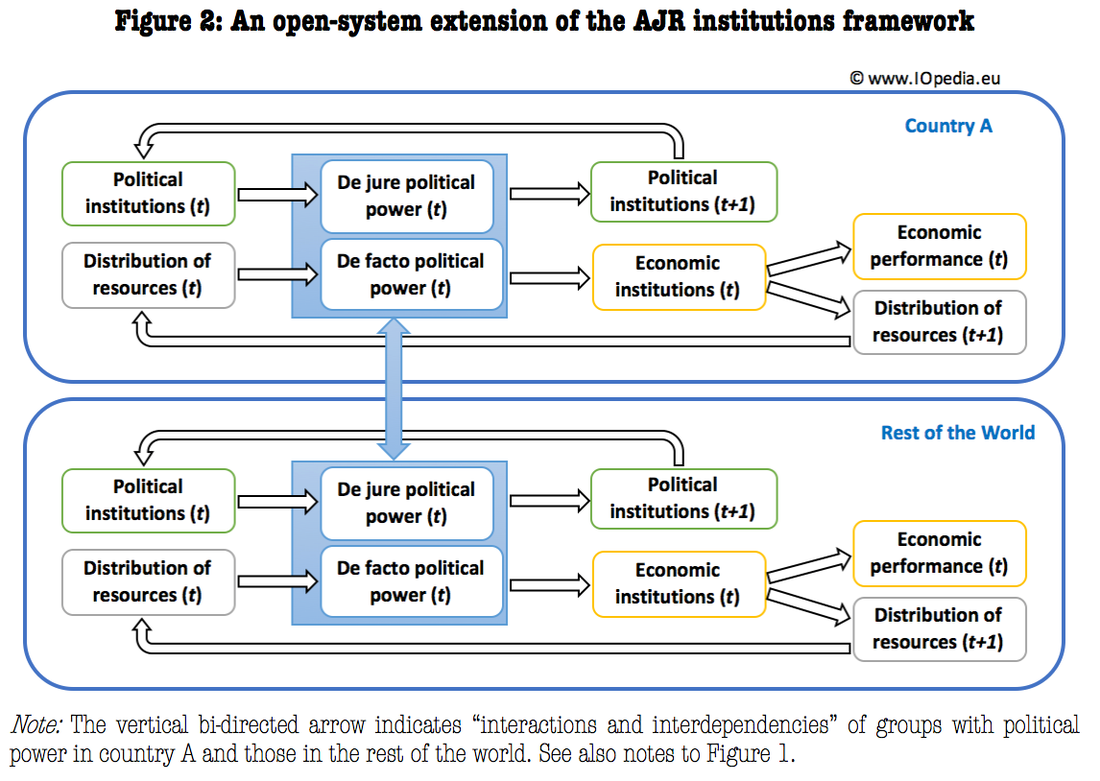

Inclusive political institutions create constraints against the exercise and usurpation of power. They also tend to create inclusive economic institutions, which in turn make the continuation of inclusive political institutions more likely… Under inclusive economic institutions, wealth is not concentrated in the hands of a small group that could then use its economic might to increase its political power disproportionately. Furthermore, under inclusive economic institutions there are more limited gains from holding political power, thus weaker incentives for every group and every ambitious, upstart individual to try to take control of the state.” – Acemoglu and Robinson (2012, Chap. 12) Notwithstanding the mentioned persistence features of the hierarchy of institutions framework, it is possible to break the vicious circles. For example, external interventions or shocks such as technological innovations (e.g. Facebook, YouTube) and international support can modify the balance of political power, affecting the whole system. Such kind of interventions can be visualized when the standard AJR institutions framework is "extended" to its open-system (or open-economy) version that allows for interactions and/or interdependencies between groups with (de jure and de factor) political power of the country in question and those of the Rest of the Word (RoW). Such a framework is presented in Figure 2 below. The extended framework may be interpreted as follows. If the groups with de jure and de facto political power in country A extensively interact with their counterparts in the RoW and the latter particularly encourage inclusive institutions, then the chances are high that the institutions in country A are also already inclusive or are in their path towards becoming more inclusive. On the contrary, if the interactions with the foreign political power are dominated by countries possessing extractive institutions, then country A will or can easily end up in a situation of cross-country vicious circles. These possibilities of cross-country interdependencies might well explain the existence of special and extensive (political, economic, social) relations among democratic countries on the one hand, and among autocratic regimes on the other. The framework in Figure 2 is particularly relevant for small countries, whose elites are more prone to political and economic pressures coming from the outside of their national borders. One of the options of breaking the vicious circles domestically is a "foreign intervention" that exercises strong pressure on domestic de jure political power and simultaneously increases domestic de facto political power of the broad cross-section of society (assuming that domestic institutions are extractive, but those of the foreign "invader" are inclusive). In general, Either some preexisting inclusive elements in institutions, or the presence of broad coalitions leading the fight against the existing regime, or just the contingent nature of history, can break vicious circles.” – Acemoglu and Robinson (2012, Chap. 13) One of the important implications of the hierarchy of institutions framework is that there must be a balance of power in society to be able to create and maintain good economic institutions, which in turn lead to good economic performance and higher living standards for all citizens. As also concluded by North, "While economic growth can occur in the short run with autocratic regimes, long run economic growth entails the development of the rule of law" (North, 1993, Nobel Prize Lecture). It must be noted that power and dominance of one group over another in terms of material and social issues as the driving forces of economic outcomes are central topics of such (heterodox) schools of economic thought as Marxian Political Economics, Feminist Economics, Post-Keynesian Economics, and Institutional Economics (for details, see e.g. www.exploring-economics.org).

Selected recommended reading: Acemoglu, D., Johnson, S. and Robinson, J.A. (2005), Institutions as a fundamental cause of long-run growth. In: Aghion P. and Durlauf S.N. (eds.), Handbook of Economic Growth, Volume 1A, Elsevier B.V, Chapter 6, pp. 385-472. Acemoglu, D. and Robinson, J.A. (2012), Why Nations Fail: The Origins of Power, Prosperity, and Poverty. New York: Crown Publishing Group. North, D.C. (1990), Institutions, Institutional Change, and Economic Performance. New York: Cambridge University Press. North, D.C. – Prize Lecture*. NobelPrize.org. Nobel Media AB 2019. Wed. 18 Sep 2019. <https://www.nobelprize.org/prizes/economic-sciences/1993/north/lecture/> Comments are closed.

|

Proudly powered by Weebly

RSS Feed

RSS Feed